Divorce Victorian style

*****SPOILER ALERT*****

You never know what you're going to uncover when you start to delve into your family history. I discovered that my great-great-grandparents, John and Eliza, were married bigamously. I was shocked, I think partly because I knew that my father would have been horrified. But subsequently, as I discovered there was quite a story behind the marriage.

Reading between the lines, and putting family stories together, it would seem that Wife I had mental health problems. Unable to get a divorce, when the only way of getting one was via an Act of Parliament, the couple went their separate ways. The children seem to have been looked after by the wife's sister, who also looked after the ex-wife when she was home. There was still contact with the father though, so it appears to have been quite an amicable arrangement. John's brother was married to Eliza's sister, so my great-great-grandfather had known her since she was a small girl. And then something terrible happened.

John's brother, Ernest, was running a wine dealership, selling high-end wines to the gentry and Members of Parliament. Eliza happened to be visiting her sister, Arabella, when an MP came to call. He was very dashing, and Arabella knew and liked his wife. Eliza who was in her mid-teens, and apparently very beautiful, was invited to visit at some point and meet the wife. It all appeared very innocent.

However....when she turned up for the meeting the wife wasn't there. Whether this was accidental or planned is not entirely clear, but what is fairly clear, if couched in extremely discreet language is that the MP sexually assaulted or, more likely, raped her. She returned to her sister distraught, Ernest promptly went out and punched the MP, who then fled back to his constituency in Ireland knowing that there was little my lower class family could do about it.

I would suspect that John then "married" Eliza in 1838, with the blessing of the first wife's family, because she feared that she was pregnant, and would be publicly shamed by what had happened. There's no record of a birth around this time, so either she lost the child, or perhaps was mistaken. There was a long period though before she had a child with my great-great-grandad. I think, and certainly hope, that he loved her, and married her to protect her.

This family story shows how limiting the laws relating to marriage and to sexual impropriety were in the England of the early nineteenth century. By 1858 much had changed, it was now possible to get divorced more easily. There were restrictions though - if you were a man, it was fairly straightforward to divorce your wife as long as you could prove adultery on her part. Private detectives were available, who weren't averse to drilling holes in walls for snooping servants to peer through. If you were a woman adultery wasn't enough, besides that you needed at least one other reason such as cruelty or desertion. It also wasn't good enough that you both wanted out of the marriage, in fact that could be grounds for not allowing you to divorce!

Against this background middle-class Isabella Robinson fell in love with society doctor Edward Lane. Isabella was married to Henry Robinson, a cold controlling man, who appears to have married Isabella mainly for her money. Robinson had a mistress and two illegitimate children. Isabella longed for love and a marriage between friends. Her liking for Lane deepened into something more, and this eventually precipitated them into a brief affair. Isabella kept a diary, and in her diary she poured out her heart - her sadness at her uncongenial marriage, her love for her children, her longing for life to offer her something more, her crushes on unsuitable men, and then her love for Edward.

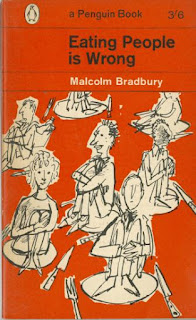

It's not clear how truthful her diary was - was it a realistic depiction of her day-to-day life, or was it how she would have liked her life to be? In Kate Summerscale's beautifully written Mrs. Robinson's Disgrace, Summerscale unpicks the story behind a divorce case that scandalised Victorian society, that was to influence a generation of Victorian novel writers, and involve a detective who would be re-imagined by Dickens and Wilkie Collins.

The affair was revealed when Isabella was taken seriously ill. Running a fever, she started to talk in her delirium, and her husband was horrified to hear her mentioning other men. He went to her room, got hold of her diary, and read it. All was revealed - her sadness, her pain, her intimacies with other men (although much of this seemed very trifling by modern standards), her husband's inadequacies as a lover. Robinson went to an ecclesiastical court to demand a separation. At first this seemed advantageous to Isabella, they could be divorced, she just had to plead guilty to adultery, there need be no mention of the co-respondent's name (vastly damaging potentially to Edward as he was a doctor, who had a large female clientele), and Isabella might even be able to keep her children. But following the divorce the law was changed, Robinson realised that there was a chance to claim damages from Lane for the loss of his wife, so he dragged the case back to the civil courts. Now, in order to save her lover, Isabella would have to convince the court that she was innocent.

In a country where books were still quite heavily censored (Madame Bovary was still banned) there would be no Fifty Shades of Grey, but reports on divorce cases could be as salacious as newspapers required. What followed must have been hugely humiliating to Isabella, while society lapped up every lurid detail. Summerscale unpicks the intricacies of the case, and lays them against a seemingly upright Victorian society, obsessed with a narrow code of conduct.

What really surprised me was how "un-Victorian" were some of the people who cross the pages of Mrs. Robinson's disgrace. For every idiotic judge who thought that putting up with cruelty was part of a woman's marriage contract, you would find a surprisingly liberal judge, such as Sir Alexander Cockburn, who according to Queen Victoria "had a notoriously bad moral character". It was Cockburn, who with a great deal of common sense and humanity found in favour of Isabella and her lover. He was also largely responsible for the tenets by which obscenity is judged in British courts even today.

While Victorian society insisted on strict moral codes, and hypocrisy and prudery was widespread, there were also the beginnings of today's sexual freedoms. Serious books about sexual health were written and circulated (usually under a pseudonym or with no author credited). There were even books about contraception, which, although still prosecuted under obscenity laws, suggested a move in society away from sex as a purely reproductive act to something more.

Women's place in a society moving towards more enlightened views remained contradictory - so liable to be shocked that they weren't allowed to listen to divorce proceedings, but also sexually avaricious beings responsible for the corruption of men. Innocents with all the wiles of a Jezebel. It's perhaps not surprising that a degree of sexual naivete combined with unrealistic expectations and entering into a contract that was hard to break meant that many men and women lived deeply unhappy lives.

This is a fascinating look into a society that was changing rapidly. Summerscale writes fact as though it was fiction, so it reads beautifully and is every bit as compelling as a good novel. I felt for Isabella, if her disgrace was partly down to her own carelessness, she comes across as a brave woman, who fought hard to protect her lover (I doubt he would have done the same for her). And although the ending, as this isn't a novel, isn't unalloyed happiness, I think Isabella came out of it well. I just hope that eventually she found happiness.

By the time my great-grandmother was born, she was sharing a house with her sister from the first marriage, so at last the families were reunited.

Comments